|

I recently had a really good work session with a student - an unexpectedly good session with a student who I think has potential, but has been resistant to almost everything we’d done in class so far this year. 5 years ago my university teaching career was blown to smithereens by a student who falsely accused me of assaulting her in an acting class - she was a student who I thought had potential, but who had been resistant to almost everything we’d done in class.* Despite her resistance, I kept trying to find a way to help her access the inner life of the scene. We went through a whole litany of exercises and techniques but never reached that moment when she connected and the scene worked. By the end of class she was frustrated and, I believe, embarrassed, and turned that into an assault allegation. I have had people tell me that I should have just stopped - if she didn’t want to do the work, I should have let her. In fact, last month another Acting professor told me that because of what I’d gone through, he and others in the field had decided that challenging students to push through acting blocks was too risky - they weren't going to put their careers on the line for a student who didn’t want to work. I thought this student had potential though, she had moments in class that were really quite good. Perhaps it was hubris on my part, but I thought I could help her. The accusation and the following events - an on campus hearing and a criminal trial, (exonerated by both, but still terminated from my position), had such a profound effect on me that I didn’t know, were I to ever get another teaching position, if I’d be able to do it. I’m not an authority on teaching Math, English or the sciences, but it seems self-evident that teaching Acting is not like being an instructor in a traditional academic discipline. For example, in beginning acting classes it’s not uncommon to spend a fair amount of time dismantling student’s preconceived notions of what they think they’re supposed to be doing, before you can even begin to build an effective, reproducible acting process. It would be great if there were one definite, definable process that would work for every student - but there isn’t. You work with vague outlines in varying modalities, trying to help your students find a way to access their emotions, creativity, and humanity. As Dr. Ross Prior states in his landmark book Teaching Actors, Knowledge Transfer in Actor Training:

In his research Prior found: “A common sub-theme emerging from the data is that acting cannot be taught; rather the ability to act can be improved or refined through experience, both in training and in professional practice. (156) and “One of the interviewees, Terry, “believed that ‘you can’t teach acting, I think you can only coach it. You know, inspire it.” (156) I think it’s really useful to hold on to this idea, that the relationship between the student and acting instructor is more similar to that of the student athlete and their sports coach, than it is to the relationship between the professor and student in a traditional classroom setting. Little wonder that administrators from those disciplines would be flummoxed by what normally happens in an Acting classroom. Despite hundreds of books being written on the subject, the definitive Acting text has not been written. There is no “one size fits all technique.” So, like most acting instructors, in my work I draw from all possible sources: Greek and Roman mask work; improvisation and commedia techniques from the middle ages; the rhetorical, literary traditions of the Renaissance; the head centered, psychological techniques of the Modern Era; and the highly physical techniques developed by post-Stanislavski practitioners such as the Polish director Jerzy Grotowski, and the Russians Meyerhold, Vakhtangov and Michael Chekhov. I come to class with a lot of tools from the pedagogical toolbox, which vary in usefulness depending upon the given situation. Robert Welker in his book The Teacher as Expert, (1992 SUNY Press) writes “Many acting coaches do instinctively what they cannot readily discuss, which suggests that tacit knowledge carries with it high levels of expertise.

So I have these teaching resources, and years of experience guiding how I apply them, but with what has occurred, I'm continually second-guessing myself. I’ve been in my present teaching position going on two years, more often than I’d care to admit, I have crushing anxiety attacks where I doubt my ability to do the job, and am frightened to my core that I’m going to say something too challenging, or do something that lands just a little wrong - and I’m going to go through it all again. I’m still here, I’m still trying, day by day to get it right, and I’m grateful for the times that it does. *If you’d like to read more, do a Google search, or go to www.shotinthefoot.weebly.com

0 Comments

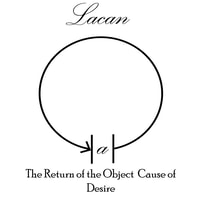

The objet petit a, and the actor's objective. While doing research for a production of Into the Woods, I ran across Tyler Matthew Howie's 2018 thesis from Boston University, A LACANIAN PERSPECTIVE ON SELECTIONS FROM INTO THE WOODS. I had never heard of this Lacan, but I was struck by how Howies explanation of of the object a petit a, mirrored how I try to explain acting objectives to my students. This is the section that I connected with: Before beginning a discussion of the objet petit a, we must first define “the other.” This is not easily done, however, as there are two “others” in Lacanian thought: the other and the Other. Klein, however, both defines the terms and describes the differences between them succinctly, saying that: …there is a distinction between the Other (capital O) and the other (lowercase o) in Lacanian thought. The Other (also called the big Other) is language and the culture that it signifies. The other, however, can be the mother, against whom the subject first defines itself, or a person who substitutes for the mother, or even an object that substitutes for the mother. In the last case, the other is also called the objet petit a (object with a lowercase a for autre: other).18 The objet petit a is the other, and serves as a replacement for the first other: the (m)other. After the subject realizes she is separate from the mother, and not connected as she was in the womb, the subject searches for a relationship, person, object, etc. that will replace the mother—or so she hopes. This search for an other to replace the mother, fueled by desire from the start, is a search that will last the subject for her entire life. However, this other, the objet petit a, is unattainable. After the subject finds what she believes to be a suitable replacement and/or substitute for the mother, she eventually realizes that said substitute is not good enough. It does not and will never fulfill the subject, closing the circuit of her desire. Lacan represents this in a graphic, shown below in Figure 1. Figure 1. Lacan’s representation of the objet petit a In this graphic, Lacan draws a line, with an arrow at one end, in the shape of a circle. The circle, however, does not connect to itself—something is blocking the arrowhead from closing the circle. That something is a lowercase a for autre—the objet petit a. The literal identity of the object does not particularly matter, but the importance of this object to the subject does. This is because the subject will never be rid of her desire for an object to complete her; the fire never goes out. Because the subject hopes for completion via the object, it is the value the subject inserts into, or projects onto the object that keeps the circle from closing. This value, however, is false; in Lacan’s view, the object can never live up to the subject’s perception of its value. The subject will never truly be satisfied, no matter what the object. Even if she does end up obtaining her objet petit a, she will realize that it does not fulfill her the way she thought it would, and will go on searching for a new one. We are never free of the search for an objet petit a. . . You can find Howie's full thesis here. This needs a lot more thought and exploration on my part - but if I didn't get it written down I was going to loose the moment's inspiration. I'd love to hear anyone else's thoughts.

The title of this piece is a declaration you find on the landing page of Sackerson Theater’s webpage. On 8/30/19, my wife and I were able to see their most recent work “A Brief Waltz in a Little Room.” I find I’m having a hard time trying to come up with the right superlatives. My most often used, “wonderful,” “awesome,” seem to only trivialize the experience. For the moment, the best word I can use to describe the experience, is “inspirational,” (but even that falls flat.) Unable to find the right explanation, let me just say that Larry West’s 19?? production of Don Delillo’s “The Day Room” was the last time I was so caught up watching a live performance in my home State.

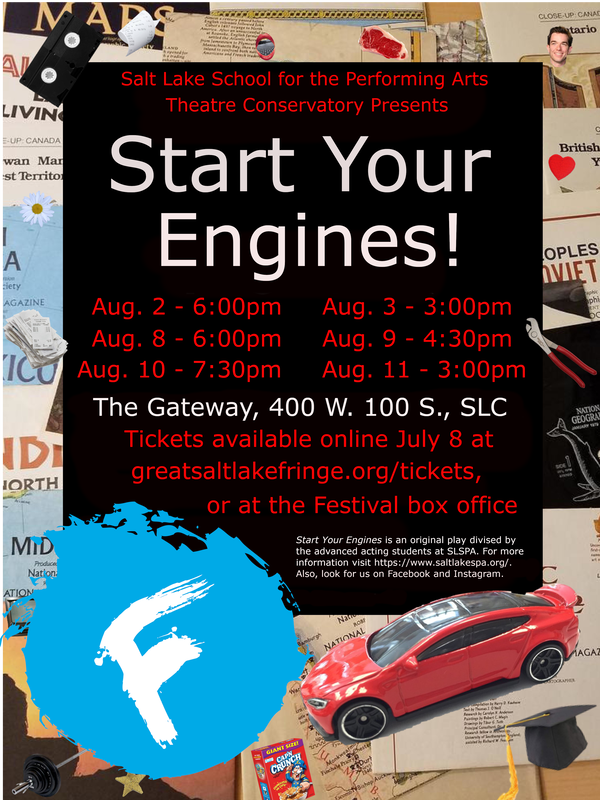

The experience, as they describe it, is this, “Ten audience members enter a hallway lined with ten doors. Behind each door: a moment in the life of Walter Eyer—an immersive human portrait; an intimate, full-spectrum pop-up installation.” With this performance event I think it would be fair to invert Sackerson’s (mission statement?) to read “Unconventional Works, New Spaces,” and for me, not knowing how bold I may be, “Willing Audiences.” I say that because as an audience member for this presentation, it may help if you leave behind preconceived ideas of what your relationship to the performance event will be. The setting, the actors, (Oh my goodness what challenging roles!), the design and execution, the direction, the concept - almost the whole experience was, as I said, an inspiration. I don’t want to impose my interpretation of the evening’s events, (I’ll edit this post when the production has closed and attempt it), but one of my favorite aspects of the evening is the meta experience, the larger context that I found between scenes. There’s one word I’ve tried to avoid in describing this show - “theater.” That is the element I missed as an audience member. Certainly it was “theatrical,” all of the necessary elements were there, audience, location, performers, a story to be told. For me though, Theater is a communal experience. One of my dearest teachers, E. Reid Gilbert, always said that theatre is one of the things that binds a community together, because it allows us to breathe together. Perhaps it was intentional - but I often felt rushed, and I never had that moment when I could comfortably look around at the other people who were there with me and acknowledge that we had just shared a wonderfully human experience. It’s in those moments of mutual acknowledgement (acceptance? understanding?) that I usually find much of the theater event’s value and power. That said - I’m so grateful to the people at Sackerson, The Umbrella Theater Company and the other sponsors for making this event happen. Change in theater rarely if ever happens in large, commercial companies. Growth and evolution bubbles up from those who have a vision, and the courage to share it. The next two weeks some of my students and I are participating in The Great Salt Lake Fringe Festival. We're taking a cut down version of Start Your Engines!, a script the advanced Conservatory class developed and produced earlier this year.

This is the 5th installment of a project called The Wasatch Cycle. Each year a different room is chosen, and the students write scenes and vignettes that occur in this not specifically located Salt Lake home. I serve as a kind of Producing Artistic Director, helping them sharpen the structure and shape the narrative - but almost all of the creative work is done by students. It makes perfect sense, but part of what I find fascinating is how these stories reflect the lives, experiences, and attitudes of my students. Almost all of them are graduating, and "what comes next" is a common question. Parenting is also frequently in their cross-hairs. Their perceptions of we "adults" are sometimes painful, sometimes hysterical, and always informative. I don't want to give too much away, because I'd like you to come and see their work, but I invite you to consider looking at this as a clear reflection of how they see the world. Like almost any other director, I'm always reading and looking for shows to do. In the back of an Introduction to Theater text I remember seeing a thought expressed that, 'If you want theatre to be important in a community, then companies should produce work that arises out of their community. They should tell stories that reflect the successes, failures, concerns and characters that are present where they live. If the companies weren't willing to take on that challenge, then they would be better off re-staging old chestnuts, or attempting to duplicate the spectacle of New York.' I was thinking that in general The Great Salt Lake Fringe Festival achieves the former objective, giving opportunity and voice to stories that, at first blush, seem like they may not resonate beyond our community or region. But then this morning I was spinning through my Facebook feed and ran into this: "Instead of bringing artists together, matchmaker-style, to adapt a movie (a process that naturally shuts out marginalized voices), producers would do better to travel to Brooklyn or regional theatres and see what artists are making. Constitution began in a 89-seat theatre in the West Village, and arose out of Schreck’s need to process her own traumatic family history. Hadestown began as a community music-theatre project in Vermont, based on Anaïs Mitchell’s love of the Orpheus myth. Both are hits because they’re damn good shows which would not work as well in any other medium; they’re authentically themselves." - Diep Tran https://www.americantheatre.org/2019/07/29/what-the-constitution-means-to-me-is-setting-a-theatrical-precedent/?fbclid=IwAR3YC-S4WpfgM18YZP0hno9DWjJQCca3VdvZlnn_OHMFNmCW1b5nFKKGdCE It leads to the interesting possibility that Fringe Festivals like this, (and they exist all over the world,) might be the key to making a more relevant, revitalized, and accessible theatre. Early Spring in 2014 I had the opportunity to attend the National Association of Schools of Theater's (NAST) conference in Chicago. At the time Dixie State was aspiring to be NAST accredited - it takes a lot of work, but puts you in the company of the best programs in the country.

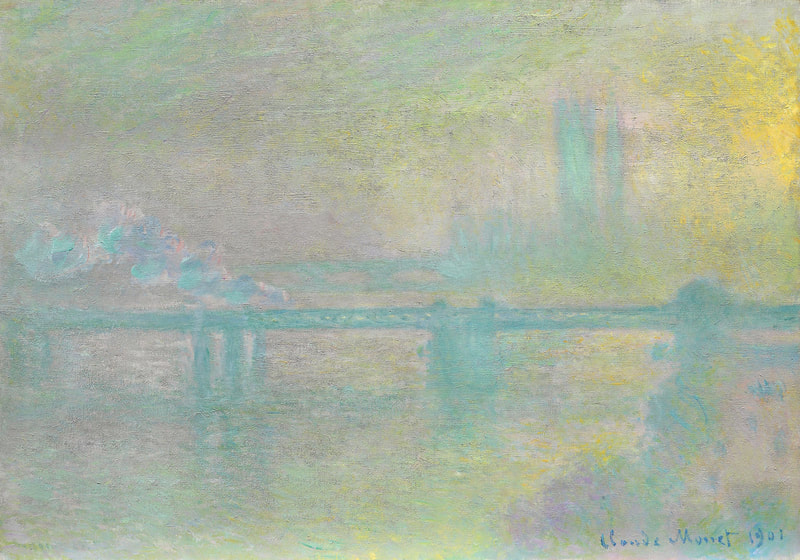

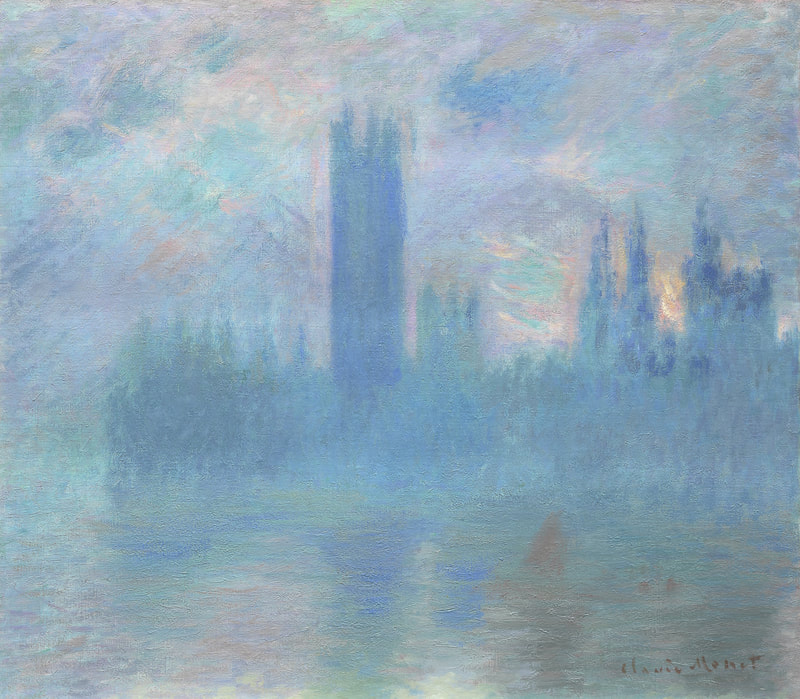

Anyway, while we were there I took a little time to visit the Art Institute of Chicago. I'd recently finished directing Sunday in the Park With George, and wanted to see the painting that inspired the musical. In terms of size, Seurat's "A Sunday on La Grande Jatte," dominates the room. But facing that huge work, my eyes kept being drawn off to the right where a series of Monet's London bridge paintings were hung. Images of Waterloo and Charing Cross bridges, Houses of Parliament. I remember thinking how stunning the paintings were and that I wish I'd had the opportunity to study with someone capable of creating such work. That is the moment when I began to understand how important productions are in theatre studies. Certainly technique matters, and can only help in producing consistent quality. Acting classes should give students the skills to navigate their way across the character map, focusing on doing the work that occurs on stage. (And why on earth had Design/Tech fallen so low on the priority list, when, like in politics, perception is reality?) Process isn't what makes students interested in your work, or by extension, interested in studying at your school. I believe classes are something many students think they have to endure, in order to get on stage and actually participate in the work. If it doesn't relate to what they'll be doing on stage, is it really relevant? Everything else is theory. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

December 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed